NAGPRA Repatriations through September 8, 2020;

Law’s Opaque Reporting Leads to Masking Objects’ Identities

by Ron McCoy

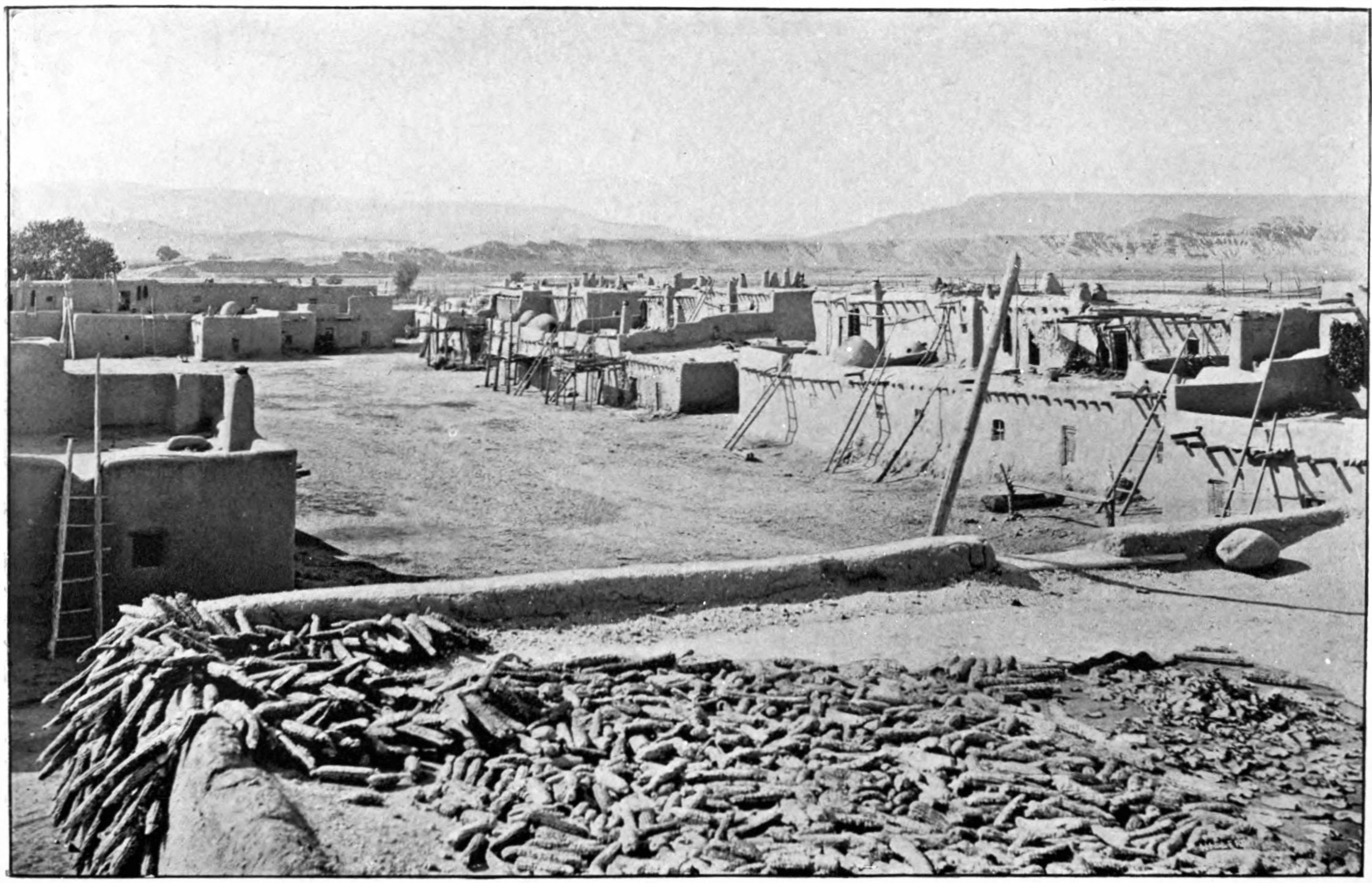

Interior of Chief Shakes House, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1990, Americans debated how best to observe (or ignore) the upcoming Columbian quincentenary. Pressed hard, Congress sought some way to signal a desire to make some amends for past practices and ongoing injustices meted out to the nation’s indigenous peoples.Its response took the form of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which lays out a blueprint for attempting to not only revisit but essentially redo the past.

The law seeks to accomplish this by establishing a process for repatriating certain types of “cultural items”[1] of Native American or Native Hawaiian origin from institutions that meet its broad definition of “museum.”[2]The rationale underlying this practice rests on the proposition that the very nature of certain objects renders them inherently involved in, forever connected to, and fundamentally inalienable from the tribal milieu. If the museum and claimant(s) — specific tribal entities or identified individuals — agree on the legitimacy of the claim, the piece will be repatriated.

In order to qualify as a cultural item under NAGPRA, a piece must fulfill the requirements for inclusion in one or more of its five categories: human remains, associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. Given this column’s anticipated readership — people who curate, collect, and deal in authentic tribal art — pieces that find their way into a pair of NAGPRA categories regularly receive attention: sacred objects[3] and objects of cultural patrimony.[4]

NAGPRA news appearing here is typically related to repatriations of materials the museums possessing them and those laying claim to them have agreed should be transferred back into the tribal sphere from which they came. That information is drawn largely from the Federal Register, sometimes augmented by additional sources. The Federal Register may not find a place on most of our reading lists, but it remains the forum of record for publishing announcements about the repatriation agreements museums and claimants arrive at through NAGPRA.

NAGPRA repatriation notices published in the Federal Register follow a standard template. That blueprint is designed to: inform readers about the identities of the institution and claimant(s) involved in the repatriation bid; provide information about a piece, its description, function, and provenance that support the case for its inherent inalienability from — and therefore the need for its repatriation to — the tribal world; and, finally, identify the person(s) or entity to which the object will be repatriated pending the filing of a competing claim. (There is no requirement under NAGPRA for any of the parties involved in the process to account for an object’s actual final disposition. A dozen tribal entities are listed in the first notice summarized below, for example, but how such a repatriation would be carried out is not this law’s concern.)

Ideally, one should be able to read a NAGPRA repatriation notice in the Federal Register and learn quite a bit about a given piece’s appearance, provenance, and role.

Each element in a NAGPRA notice is important, but a point of particular concern and interest is that part in which the object to be repatriated is described. That is because for this column’s intended audience, knowledge about a piece’s construction, appearance, and provenance is of vital importance if they are to understand how the letter and spirit of the law are reflected through its application.

This current harvest of NAGPRA notices of intent to repatriate sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony brings us up to date on those appearing in the Federal Register through September 8, 2020. (Unless otherwise indicated, quotations used in reporting notices comes from those notices.)

Diegueño/Kumeyaay Basketry Feathered Shaman’s Hat

Sacred Object

Museum of Riverside, Riverside, CA (Sept. 8, 2020): The item covered by this repatriation notice, otherwise undescribed, is a “basketry feathered shaman’s hat” dated to circa 1900, a “sacred item [which] was removed from the traditional land of the Diegueño/Kumeyaay in San Diego County, CA.”No additional information supports that conclusion, and the piece’s provenance evidently consists of a 1952 letter documenting its donation to the institution.

The museum agreed to transfer the hat to a group of culturally related California entities referred to collectively as “The Tribes” for purposes of the notice: the Campo Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Campo Indian Reservation; Capitan Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians (Barona Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Barona Reservation); Viejas (Baron Long) Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Viejas Reservation); Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians; Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel; Inaja Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Inaja and Cosmit Reservation; Jamul Indian Village; La Posta Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the La Posta Indian Reservation; Manzanita Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Manzanita Reservation; Mesa Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Mesa Grande Reservation; San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians; and the Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation.

Painted Drum (Cochiti Pueblo)

Sacred Object/ Cultural Patrimony

Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX (July 30, 2020): This notice focuses on a painted wooden drum acquired by California attorney Erle Stanley Gardner (1889-1970), who achieved fame as the prolific creator-chronicler of fictional courtroom lion Perry Mason. We know nothing about this drum, other than that fact of its donation to the museum as part of Gardner’s estate and the piece’s general appearance: “a wooden drum with rawhide ends and lacing, and painted in ochre, dark brown, and white colors.”

According to the notice, “research and consultation with representatives from the Pueblo of Cochiti, New Mexico, found that Cochiti is known by all Pueblos for creating ceremonial drums of this style for tribal use in the practice of traditional native religion.” (Cochiti is also known for producing drums for the marketplace.) “Accordingly, this drum…clearly is a sacred object originating from Cochiti Pueblo,” to which the museum agreed the drum should be repatriated.

By combining this notice with an interesting firsthand account of the process written by Ester Harrison, a member of the museum’s staff, it is possible to glean some insight into how this decision was made.[5]

Basically, after the museum figured out the drum was likely of Native American origin, probably from the Southwest, the instrument was included in a 2019 summary of possible NAGPRA-affected objects in its collections. About a year later, Harrison writes, “we were delighted to hear from the Cochiti Pueblo in New Mexico who positively identified one of the drums in the inventory as being Cochiti and an object of cultural patrimony.”[6] After that, “[w]orking closely with the Cochiti Pueblo contact primarily by telephone, we supported each other through the required next steps, sometimes sharing each other’s views and experiences and embarking on a meaningful new professional relationship in the process.”[7]

Killer Whale Shirt (Tlingit)

Sacred Object/ Cultural Patrimony

Minnesota Museum of American Art, St. Paul, MN (June 10, 2020): In 1926, Presbyterian minister and teacher Axel Rasmussen (1886-1945) commenced a decade-long tenure as superintendent of schools in Wrangell, Alaska, subsequently taking up a similar posting in Skagway.[8] Over the years, Rasmussen, a keen student of Tlingit and other regional cultures, put together a substantial collection of pieces from the area’s indigenous peoples. Among his acquisitions is the piece to which this notice refers: a killer whale shirt, which the Minnesota Museum of American Art bought from the Portland Art Museum in 1957.

This shirt is associated with the Naanya.aayí clan, which serves as its collective custodian. Tribal representatives “described how the clan came to own the name and crest killer whale Sheiyksh, and demonstrated the traditional uncle-to-nephew hereditary transfer of the item going back to the first Chief Shakes.” (A photograph taken in the early 1940s shows Chief Shakes VII, also known as Charlie Jones, wearing this shirt.)[9]

The writer(s) of this notice took pains to emphasize the nature of the bonds linking the Naanya.aayí clan to this shirt. “The killer whale shirt bonds the Tlingit people to their ancestors,” the author tells us, “symbolizing the people’s relationship to the being depicted on it.” The prominent inclusion of the clan crest in the garment’s overall design “provides a physical form in which spiritual beings manifest their presence.”

The notice finds this shirt is “needed for current and ongoing cultural and religious practices,” and, further, that “under the Tlingit system of communal property ownership, it could not be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by any individual.”

Accordingly, the museum agreed to return the killer whale shirt to the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes, acting for itself and on behalf of the Wrangell Cooperative Association (specifically the Naanya.aayí clan).

5,816 Objects (Winnebago)

Cultural Patrimony

John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI (June 10, 2020): Watchmaker and amateur archaeologist Rudolph Kuehne (1855-1929)[10] amassed a large trove of objects during some thirty-five years of digging and scraping in and around Sheboygan, Wisconsin. The collection he built contains nearly six thousand objects, including: stone points, scrapers, hand axes, hammerstones, gorgets, beads, and gaming pieces; copper points, blades, awls, amulets, beads, and rings; antler awls; also clay vessels, plant specimens, and seven beaded sashes or belts.[11]

After Kuehne’s death, the museum’s parent entity acquired this material from his widow.

The museum agreed these cultural items qualified as objects of cultural patrimony under NAGPRA and should be transferred to the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, whose ancestors resided in the Sheboygan area.

Eleven Objects “Erroneously Identified…as Masks” (Navajo)

Sacred Objects

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Art Theft Program, Washington, D.C. (June 10, 2020): At a time unknown, “11 sacred objects were acquired in the Southwest and transported to the East Coast.” There, these eleven undescribed pieces became “part of a private collection of Native American antiquities, art and cultural heritage.” In the spring of 2018, the FBI, acting in connection with a criminal investigation, seized those objects, which had been “erroneously identified by the collector as masks.” (For the moment, let us leave aside the question of what these pieces might be; after all, the notice tells us their identification as masks would be erroneous since they are obviously not masks.) The FBI determined these pieces are sacred objects that rightfully belong with the Navajo Nation of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah.

If you are left a bit confused wondering what this notice is about, you are not alone.

In what appears to be a growing trend with NAGPRA notices, the author(s) of this entry opted for opacity by providing as little information as possible. Whether done intentionally or unconsciously, this renders the notice practically worthless for tribal art curators, collectors, and dealers in their attempts to discern the shifting parameters of the objects embraced by NAGPRA. The situation here is rendered patently absurd, because the eleven objects “erroneously identified by the collector as masks” are almost certainly eleven masks.

How did we arrive at the point where such a conclusion seems to be the only one that is even remotely reasonable?

We receive the message these objects are masks because the notice takes great pains to inform us they are not masks. The author(s) of the notice manage to attain this questionable goal by emphasizing that the objects were “erroneously identified by the collector as masks [italics added].” If these pieces are not masks, what are they? Baskets? Quillwork? Rattles? Pottery? It seems perfectly reasonable to conclude that what a collector “erroneously” identified as masks must have looked to her/him a lot like…masks.

“What’s in a name?” William Shakespeare’s Juliet asks her Romeo. After all, she asserts: “That which we call a rose/By any other name would smell as sweet.”[12] (It might be helpful to recall that, like the rest of Romeo and Juliet, the words the bard placed on Juliet’s lips form part of a tragedy.) Some three centuries later, modernist writer Gertrude Stein reminded readers: “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”[13] But obscuring the identity of a mask by failing to even describe it properly — while simultaneously asserting someone “erroneously identified” it as a mask — constitutes an act of masking.

It seems likely this masking exercise was intended to address the sensibilities of people for whom describing certain objects as “masks” would be problematic. However worthwhile that goal may be, in this instance the act of bending to it eliminates the possibility of presenting meaningful information about the pieces. Even Shakespeare and Stein, when talking about roses, did not use esoteric code; instead, they used a specific, readily understood word — that word was “rose” — so readers would know what they were writing about. In that vein, here is a suggestion for NAGPRA notice writers: Instead of muddying the waters, why not consult a list of appropriate synonyms for “mask”? In the meantime, let me suggest one: “not-mask.”

NAGPRA, like any law, is credible only so long as it is understood. Obscuring the identity of objects slated for repatriation is a profoundly unhelpful act, one which falls well outside the goal of keeping us informed about how the law is enforced.

Please note: This column does not offer legal or financial advice. Anyone requiring such advice should consult a professional in the relevant field. The author welcomes readers’ comments and suggestions, which may be sent to him at legalbriefs@atada.org

ENDNOTES

[1] “Cultural items” under NAGPRA means: “Human remains, associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, [and] cultural patrimony.” “Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: Glossary,” National Park Service (2020), https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/glossary.htm

[2] For NAGPRA’s purposes, a “museum” refers to “[a]ny institution or State or Local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds an has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items.” Ibid. Specifically excluded: “the Smithsonian Institution or any other Federal agency,” which are covered by other legislation.

[3]For NAGPRA’s purposes, a “sacred object” is “needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day [sic] adherents.” Ibid.

[4] An object is deemed “cultural patrimony” under NAGPRA if it has “ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or cultural itself, rather than property owned by an individual Native American, and which, therefore, cannot be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by any individual regardless of whether or not the individual is a member of the Indian tribe or such Native American group at the time the object was separated from such group.” Ibid.

[5] Ester Harrison, “The Ransom Center and NAGPRA: A Team Effort in Research,” Ransom Center Magazine (2021), https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/2021/02/18/the-ransom-center-and-nagpra-a-team-effort-in-research/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Bill Mercer, “Native American Art at Portland Art Museum,” American Indian Art Magazine, Vol. 26, No. 2 (74-81), 76-79; “Beloit College Collections,” (n.d., accessed May 2, 2019). https://dcms.beloit.edu/digital/collection/logan/id/3274/

[9] The information accompanying the photograph labels the garment worn by Shakes VII the “Killer Whale Flotilla Robe.” “Chief Shakes VII,” Alaska’s Digital Archives (Alaska State Library – Historical Collections), https://vilda.alaska.edu/digital/collection/cdmg21/id/2418/

[10] “Emma Greiser Kuehne,“ Find a Grave (2021). https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/101993518/emma-kuehne

[11] At the time, The Wisconsin Archaeologist, NS, Vol. 9, No. 3 (April 1930) (The Wisconsin Archeological Society), 143, described Kuehne’s collection as “one of Wisconsin’s richest and most valuable private archeological collections.”

[12] Romeo and Juliet, Act II Scene II REDO “The Complete Works of Shakespeare,”

http://shakespeare.mit.edu/romeo_juliet/romeo_juliet.2.2.html

[13] In her 1913 poem “Sacred Emily” (1913), Stein wrote: “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” Later, in Operas and Plays (1932), she recalibrated her remarks: “Do we suppose that all she knows is that a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” “Gertrude Stein,” EPC Digital Library (Electronic Poetry Center, 2011), http://writing.upenn.edu/library/Stein-Gertrude_Rose-is-a-rose.html