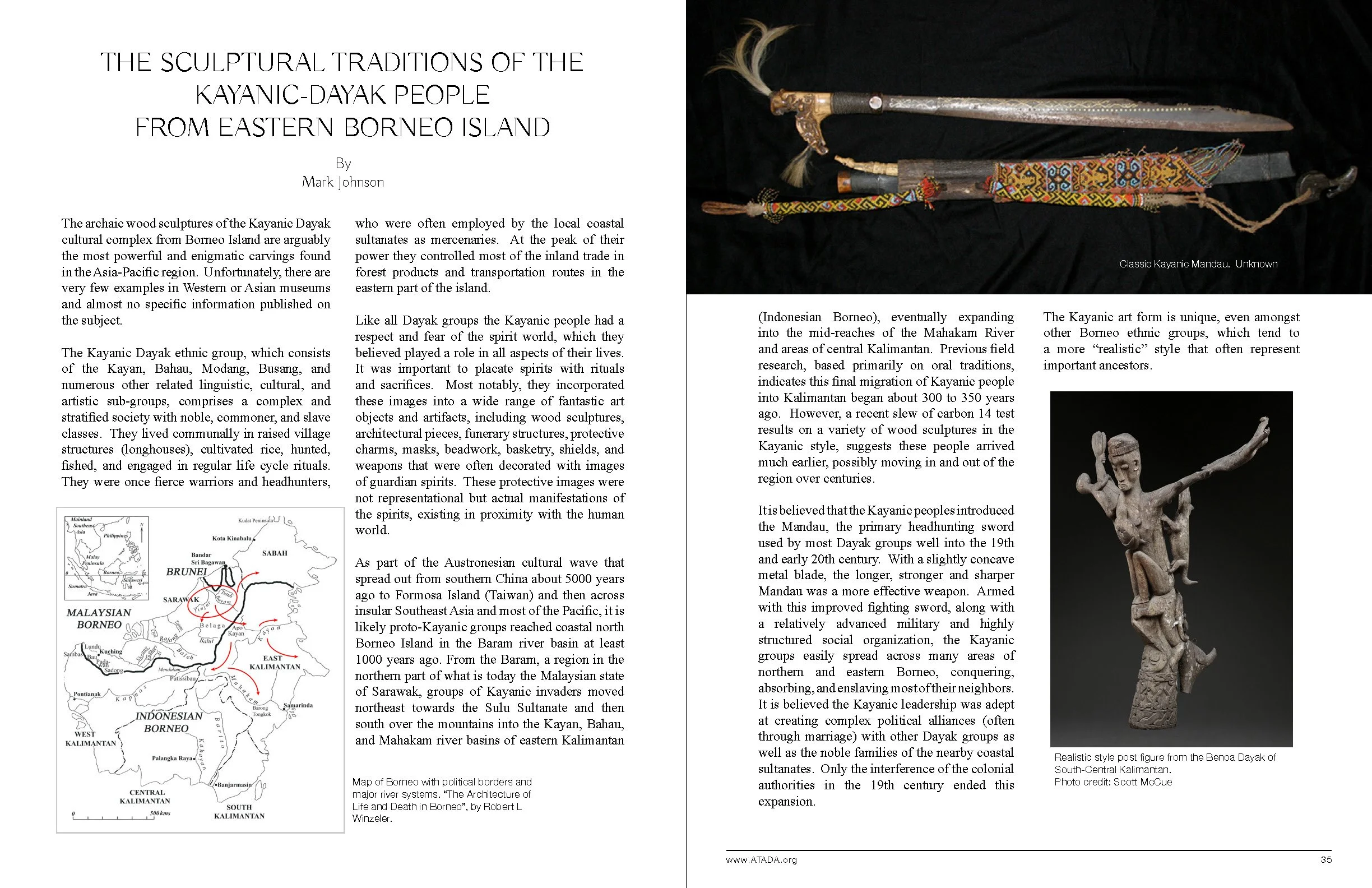

ATADA: Protecting the Past. Shaping the Future.

An organization OF and FOR collectors, dealers, and enthusiasts of the world’s traditional arts

Welcome Back to the ATADA Newsletter!

It’s been a while since the last issue, and a lot has changed. We’ve said goodbye to some dear friends and welcomed new faces into our circle. ATADA is always growing and shifting. We are a living community made up of many voices.

We know that at times ATADA may have felt a little disconnected, but it’s so much more than just standing up to legislation. At its heart, this organization is about people: collectors and dealers, colleagues and clients, all coming together over a shared love.

In this issue, we want to remind you of what ATADA is, what it can be, and how you can be a part of shaping it. Most of all, we invite you to stay connected. Share your thoughts, your ideas, and your energy with us. We are excited to continue this journey together!

We Want to Hear from You!

What do you want to see in the newsletter?

Do you have an article you’d like to submit?

Have you PUBLISHED or AUTHORED a book or article? We want to link to you!

Do you know of an event you’d like to get on the calendar?

Is there a question you’d like answered in a future issue?

Send us a note at: newsletter@atada.org