by Ron McCoy

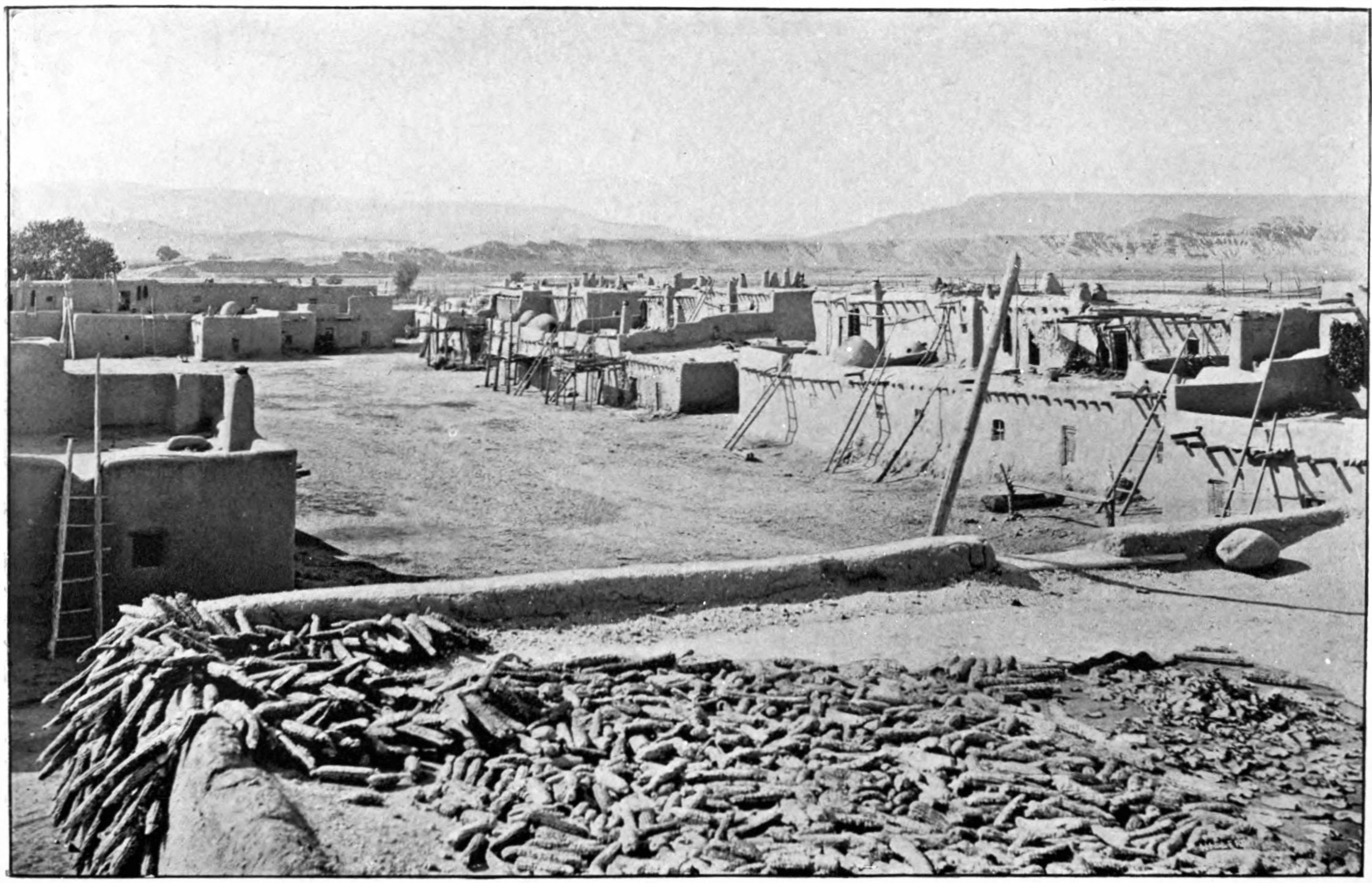

The Tewa Pueblo at San Juan, via Wikimedia Commons

As readers of this column know, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which the U.S. Congress passed and President George H.W. Bush signed into law back in 1990, continually ripples through the small universe of the tribal art world’s dealers, collectors, and curators.

This is because NAGPRA came weaponized with a mandate for effecting the repatriation of particular types of materials from certain institutions to American Indian and Native Hawaiian tribal entities and individuals. The institutions involved are those which fall within NAGPRA’s broad definition of “museums.” The items in question are those which meet the law’s requirements for inclusion within its “sacred objects” and/or “objects of cultural patrimony” categories. In such cases, the operating theory is that an object’s removal from the tribal sphere was illegitimate from the get-go, which makes restitution the logical remedy.

Like many of you, I’ve become concerned over the years by what seems to be, increasingly, an over-broad interpretation of NAGPRA’s sweep and scope as originally intended, coupled with a disturbing reliance on arriving at conclusions with the help of “self-evident” evidence which is anything but self-evidentiary. It is difficult to see these developments as anything other than a significant detour on the road NAGPRA’s originators thought they laid out back in the day when MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This” leaped onto the Billboard hundred hot-singles list.

That was then and this is now. My sense that NAGPRA is becoming increasingly and uncomfortably non-transparent is a topic I hope to explore here soon.

For now, it’s time to catch up on those notices of intent to repatriate items that appear on an irregular basis in the Federal Register. These notices reflect an agreement between the institution holding a piece and a claiming party as to whether the item is a sacred object and/or object of cultural patrimony under NAGPRA. The notice stipulates to what/whom the piece will be repatriated, pending a competing claim lodged in response to the notice’s publication.

The notices summarized here, which bring the summaries as they appear in “Legal Briefs” up to the end of April 2019, are listed in the most-to-least-recent order as published in the Federal Register; all quotes come from those notices.

Tlingit/Haida S’aaxw (Hat) and Keet Koowaal (Killerwhale with a Hole in its Fin)

• Objects of Cultural Patrimony

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL (April 29, 2019): The two pieces addressed in this notice were obtained at Wrangell, AK, by Axel Rasmussen, who worked as a school superintendent there and at Skagway from the late-1920s until his death in 1945.[1] The pieces are, basically, undescribed. However, we do learn from this notice that they consist of a S’aaxw (hat) purchased from another museum in 1956, and a Keet Koowaal (Killerwhale with a Hole in its Fin) which found its way to the institution through purchase from an art gallery. The museum determined these pieces were objects of cultural patrimony that legally belonged with the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes in Alaska.

Trunk of Omaha “Medicinal Bundles”

• Sacred Object

Nebraska State Historical Society, DBA History Nebraska, Lincoln, NE (April 24, 2019): Charles Amos Walker, an Omaha, was fourteen when he arrived at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1908.[2] Later, he became the first chair of the Omaha Tribal Council, on which he served for more than a quarter-century. In 1962, over fifty years after he showed up at Carlisle, Walker gave the state historical society “a trunk containing medicinal bundles” previously in the possession of his grandfather.[3] In a letter, he asked the institution to preserve the “Indian relic known as bundle.”

The historical society “first initiated consultation on this collection by sending a NAGPRA summary to the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska in 1993.” However, the notice indicates it did not hear about Walker’s trunk until 2018, when a lineal descendant of his asked for it to be repatriated as a sacred object.[4] The institution agreed the trunk of “medicinal bundles” Charles Walker entrusted into the museum’s care “contains specific ceremonial objects needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present-day adherents,” which should be turned over to Walker’s lineal descendant.

Tolowa Dee-ni’ Basketry and Other Materials

• Sacred Objects/Objects of Cultural Patrimony

San Diego Museum of Man, San Diego, CA (Feb. 8, 2019): Between an unknown date and 2002 the museum was given, purchased, or obtained through exchange the forty-nine objects covered by this notice. Most of the pieces consist of basketry – ten mush baskets plus others created for cooking, storage, and various additional purposes, are defined as objects of cultural patrimony; nineteen basket caps qualified as sacred objects – while other types of articles include: a buckskin headband decorated with red woodpecker and cormorant or mallard feathers; an otter-skin quiver; and a buckskin dress decorated with abalone shell and glass beads.

Representatives of the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation, previously referenced as the Smith River Rancheria, “informed the Museum that the items identified…as sacred objects are needed by present-day religious leaders for use in modern day religious ceremonies by the Tolowa Dee-ni’ adherents, including the Naa-yvlh-sri-nee-dash (World Renewal Feather Dance), the Ch’a-lh-day wvn Srdee-yvn (Flower Dance), and the Shin-chu Nee-dash (Summer solstice Nee-dash).” In addition, the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation regards those pieces identified as objects of cultural patrimony as “communally owned by the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation…and to be inalienable by any individual.”

The museum agreed all of these objects should be repatriated to the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation in California.

Tlingit Baskets and Other Material

• Sacred Objects/Objects of Cultural Patrimony

George Fox University, Newberg, OR (Feb. 8, 2019): This notice references twenty-six objects, which, between 1880 and 1920, “were removed from [the Tlingit settlement at] Kake, AK, by missionaries and others visiting the area from Quaker congregations in Oregon.” (The Quaker connection here is attributable to the denomination’s founding of the university in 1885.)

The collection includes ten baskets (one with beading), two wooden carved canoe paddles, three miniature paddles, a model canoe, face from a totem pole, bone ladle, “one medicine man mask, one rattle used by medicine man, Rattle/Charm with Eagle and killer whale design,” as well as other pieces.

The notice explains that the NAGPRA and Historic Properties coordinator for the Organized Village of Kake “was able to identify unique weaving patterns and other details indicating that items were from Kake, and were created by members of the Tlingit tribe.” In addition, he “has revealed the identity of these items.”

The museum decided to return the twenty-six objects to the Organized Village of Kake in Alaska.

Haudenosaunee Wampum Belt

• Object of Cultural Patrimony

New York State Museum, Albany, NY (Feb. 8, 2019): During the late 19th century, the museum acquired many Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) pieces through the efforts of Harriet Maxwell Converse 1836-1903), a dedicated folklorist, passionate poet, and indefatigable defender of Indian rights. One of these is the two-feet-wide, two-inch wide Ransom wampum belt, which consists of rows of purple and white shell beads.

In 1899, Converse stated she obtained the belt “from a direct descendant of Mary Jamieson [Jemison] – the celebrated white woman captive – in whose care it had been placed by the Senecas. She guarded it till her death, when it reverted to her heirs, by whom it has been held until now – the fourth generation. It is one of the national belts of the Senecas.”[5]

That said, the notice stipulates that Converse “identified the Ransom wampum belt as ‘Onondaga’…[and] reported that this wampum belt was used by women to spare the life of a prisoner [like Jemison]. As such, the Ransom wampum belt symbolizes the role of women in the adoption of captives.”

The museum concluded “the Ransom wampum belt is an object of cultural patrimony, as it relates to the functions of a Council” and should be transferred to the Onoondaga Nation in New York.

Yaqui Deer Head

• Object of Cultural Patrimony

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Law Enforcement, Rio Rico, AZ (Feb. 8, 2019): At the end of January 2018, according to the notice, “one cultural object was seized at the Port of Entry in Nogales, AZ.” This was “identified by the Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona as a Yaqui ceremonial deer head,” which the parties involved agreed was an object of cultural patrimony rightfully belonging to the Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona.

Osage Life Stick, Tattooing Needle, and Stick Bundle

• Objects of Cultural Patrimony

St. Joseph Museums, Inc., St. Joseph, MO (Feb. 8, 2019): This notice focuses on three pieces, all of them of Osage origin and each from the Harry L. George collection at the St. Joseph Museum. In 1915, George, a St. Louis businessman, purchased an “Osage Life Stick” for $12.50 from Nebraska collector Vern Thornburgh, an item identified by noted American Indian ethnographer Francis La Flesche (1857-1932) as a ceremonial piece that formerly belonged “to one of the Buffalo clans of the Osage tribe.” The next year, George shelled out $10 to the Indian Curio Company of Oklahoma City for what research indicated was a tattooing needle removed from an Osage sacred bundle.[6] At a time unknown, George hit something of a trifecta in terms of NAGPRA when he obtained a bundle of counting sticks identified by representatives of the Osage Nation as “a consecrated item.” These pieces, all considered objects of cultural patrimony, were slated for repatriation to the Osage Nation in Oklahoma.

Two Kumeyaay Groundstone Pestles and One Ecofact[7]

• Sacred Objects

San Diego Museum of Man, San Diego, CA (Feb. 4, 2019): During the three decades that elapsed between the 1920s and 1950s, the museum removed more than 1,500 objects while conducting archaeological reconnaissance of a site in San Diego County, California. Three pieces in that array – two groundstone pestles and an ecofact (identified as such but not otherwise described) – qualified as sacred objects “needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present-day adherents.” Accordingly, these items were scheduled to be repatriated to the Kumeyaay Nation.

Tolowa Mush Bowl (Xaa-ts’a’)

• Object of Cultural Patrimony

Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, CA (Dec. 6, 2018): In 1974, the museum received a 4-inch tall, 8-inch wide mush bowl “woven from twined bear grass with a diamond pattern.” Sometime during “the 19th or 20th century…[it] was removed from an unknown location in California.” Representatives of the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation (formerly designated as the Smith River Rancheria, California) and the Yurok Tribe of the Yurok Reservation, California, identified the piece as Tolowa. The museum agreed the basket qualified as an object of cultural patrimony, one imbued with “ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or cultural itself, rather than property owned by an individual.”

It was agreed to turn the mush bowl over to the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation in California, which includes the Campo Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Campo Indian Reservation; Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of California (Barona Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Barona Reservation); Viejas (Baron Long) Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Viejas Reservation; Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians; Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel; Inaja Band of Diegueno Indians of the Inaja and Cosmit Reservation; Jamul Indian Village; La Posta Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the La Posta Indian Reservation; Manzanita Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Manzanita Reservation; Mesa Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Mesa Grande Reservation; San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians; and the Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation, all located in California.

San Juan Pueblo Prayer Stick

• Sacred Object

Riverside Metropolitan Museum, Riverside, CA (Aug. 23, 2018): In 1985, the museum was given a carved wood prayer stick, for which we are offered no further description. The year the donor obtained this object and the circumstances of its acquisition are not set forth, but its decorative elements include, at one end, an inscription written in orange ink: “John Trujillo/San Juan Pueblo.” It was agreed this prayer stick is a sacred object; that is, “a specific ceremonial object needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present-day adherents.” The museum agreed to transfer the prayer stick to San Juan Pueblo in New Mexico.

Please note: This column does not offer legal or financial advice. Anyone requiring such advice should consult a professional in the relevant field. The author welcomes readers’ comments and suggestions, which may be sent to him at legalbriefs@atada.org

Endnotes:

[1] “Beloit College Collections,” (n.d., accessed May 2, 2019). https://dcms.beloit.edu/digital/collection/logan/id/3274/

[2] “Charles Amos Walker Progress Card,” Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, Archives & Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA (n.d., accessed May 15, 2019), http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/student_files/charles-amos-walker-progress-card

[3] According to the notice, Charles A. Walker’s grandfather was Alan Walker, who was born around 1838 and reportedly died in 1907.

[4] For an interesting account by that descendant, Marissa Miakonda Cummings, see her “Speaking to the Future, Honoring the Past,” OmahaMagazine.com (Aug. 26, 2016), https://omahamagazine.com/articles/marisa-miakonda-cummings/

[5] William M. Beauchamps, “Wampum and Shell Articles Used by the New York Indians,” Bulletin of the New York State Museum, No. 41, Vol. 8 (Eb. 1901), 407. In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Mary Jemison (1743-1833), a Scots-Irish immigrant, was captured by a Shawnee-French raiding party in central Pennsylvania. At Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh), Mary was acquired by Senecas, members of group with whom she remained for the rest of her long life. Jemison’s story provided minister James E. Seaver with grist for one of the early, classic captivity narratives: James E. Seaver, A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, first published in 1824 and still in-print.

[6] For insight into the the various aspects of Native American tattooing, including the practice as a sacral act, see Aaron Deter-Wolf and Carol Diaz-Granados, eds., Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

[7] “Ecofacts are not made by humans, which is what distinguishes them from artifacts. They are, instead, naturally occurring and unmodified materials used by humans. Spanish moss used as bed lining would be an example of an ecofact. A tree branch picked up and used as a back scratcher would be an ecofact. The remains of the deer you shot and ate would be ecofacts.” Laurie A. Wilkie, Strung Out On Archaeology: An Introduction to Archaeological Research (Routledge: London, 2014), 43.